Eliminating Unacceptable Forms of Work: A global challenge

An increasing proportion of the world’s labour force is working in conditions of insecurity, low pay and inadequate social protection. In the wake of the global economic crisis, precarious jobs have proliferated in advanced industrialized countries. In settings where informal work has long been widespread, many jobs are of very low quality and there are signs that formal jobs are increasingly being casualized. With the current economic slowdown, gains made by workers in emerging and developing economies are at risk. Further, certain groups — such as women, migrant workers, young workers and ethnic minorities — are more likely to be found in precarious work. The elimination of unacceptable jobs is therefore a crucial challenge in ensuring human rights for the global community.

Unacceptable Forms of Work: A new policy agenda

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has responded to this challenge by identifying Unacceptable Forms of Work (UFW):

[W]ork in conditions that deny fundamental principles and rights at work, put at risk the lives, health, freedom, human dignity and security of workers or keep households in conditions of extreme poverty (ILO 2013, para 49).

ILO has called on policy makers to take immediate action to eliminate or improve UFW.

Yet identifying the priorities and targets of policy interventions, and the most effective strategies, is not straightforward.

Recent research commissioned by the ILO has proposed such a model.1

The Multidimensional Model of UFW

It is our argument that to tackle UFW effectively, the full range of dimensions in which work can be unacceptable must be recognized. Such a multidimensional approach allows policymakers in a wide range of settings to target the UFW that are most widespread or detrimental and to decide on priorities for action.

To this end, our research has proposed a Multidimensional Model that can be used to identify and eliminate UFW. This model:

- Identifies 12 dimensions of unacceptability;

- Empowers local actors to determine priorities for intervention;

- Proposes a strategic approach to ensure that UFW policies have wide-ranging and sustainable effects.

Social Protection and the 12 Dimensions of UFW

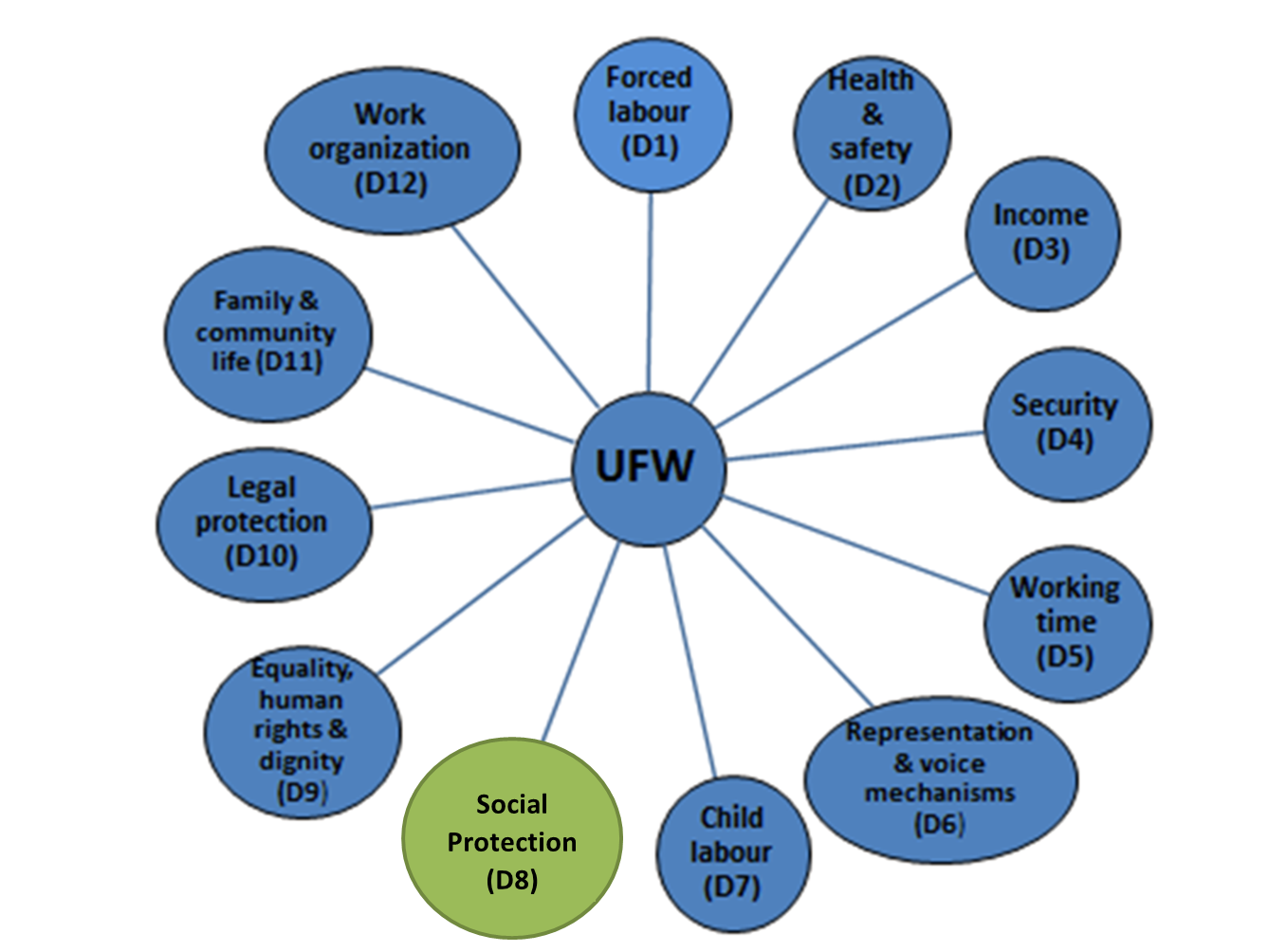

The Multidimensional Model is designed to capture the range of dimensions in which work can be unacceptable. These include income, security, working hours, representation and voice mechanisms, and forced labour, among others (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The substantive dimensions of UFW (Fudge and McCann 2015)

Lack of social protection is a crucial element of this model. Social protection is too frequently treated separately from other dimensions of working life. In contrast, the Multidimensional Model singles out social protection as a dimension of UFW. It embraces the key entitlements of effective social protection frameworks, for instance: health care, pension coverage, family support and unemployment insurance. Jobs are considered unacceptable when social protection is inadequate to satisfy basic needs.

Social protection is designated as “fundamental”: its deficiencies must be addressed as a matter of priority. It is crucial, further, that efforts to address UFW reflect the international norms. In this regard, the Multidimensional Model explicitly aligns with the ILO standards, including the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention 1952 (No. 102) and the Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202).

How to Eliminate UFW

Traditional policy and regulatory mechanisms are unlikely to be successful in eliminating UFW. Instead, new social and economic policies that specifically target unacceptable jobs are essential. While priorities and strategies will inevitably vary from country to country, certain key principles are applicable across the globe.

The central role of local policy actors

The socio-economic, governance and labour market factors that help to shape UFW, and the forms of intervention that will be effective in combatting it, are highly complex. It is therefore crucial for local actors (governments, social partners and civil society) to be involved. Policy actors must play a central role in mapping the magnitude and complexion of UFW, discerning patterns, such as the concentration of UFW among certain groups of workers or sectors, and identifying priorities for intervention.

Strategic regulation of UFW

In targeting UFW, a strategic approach is essential. This involves identifying the most widespread and severe forms of UFW. It also involves gauging whether an intervention is likely to generate substantial and sustained effects that have the potential to spread to other parts of the economy.

Weil has suggested criteria for such a strategic approach: prioritization, deterrence, sustainability, and systemic effects.2 Building on Weil’s work, Fudge and McCann’s research on UFW points to the need to target interventions at ‘points of leverage’ that are likely to generate broader effects.

Two regulatory interventions that have effectively addressed UFW are the regulation of Mathadi work in India and of domestic work in Uruguay.

Mathadi workers are head-load carriers in the state of Maharashtra in India. Since 1969, the Mathadi Act has regulated the conditions of these workers and provided social protection.

The Act established tripartite Mathadi Boards that set living wages. These Boards also administer pension funds and workers’ compensation, and provide medical care and educational assistance for workers and their families.

The Act has been successful in formalizing Mathadi employment, increasing wages, lifting workers and their families out of poverty, and providing insurance against a range of risks.

In 2006, Law 18.065 entitled Uruguayan domestic workers to the same labour and social security rights as other workers. The law set a minimum working age of 18 years and recognized domestic workers’ rights to e.g. a 44-hour week, tripartite wage negotiation, and unemployment insurance.[/one_half]

Table 1 Strategic regulation in action (adapted from Fudge and McCann 2015)

These models are not perfect, nor directly transferable to other settings without adjustment. Yet they provide useful examples of interventions that have produced beneficial effects for workers in UFW, including in the social protection dimension.

Towards a global dialogue on innovative UFW policies

To conclude, global experimentation with the strategic regulation of UFW is urgently needed. Equally, the lessons derived from innovative policies must be circulated among policy-makers and researchers across the world. Sharing of ‘best practice’ is crucial to disseminating new ideas and successful strategies (see for example, the Global Dialogue on UFW). Innovative methods can be tested, refined and adjusted for introduction in new settings. Such an international dialogue is essential to stemming the further expansion of UFW, improving and eliminating unacceptable jobs, and thereby advancing the global ideal of decent work.

References

Judy Fudge and Deirdre McCann, Unacceptable Forms of Work: A Global and Comparative Study (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2015).

International Labour Organization, The Director-General’s Programme and Budget Proposals for 2014-15 (Geneva: ILO, 2013).

David Weil “A Strategic Approach to Labour Inspection” 147(4) International Labour Review 147 (2008): 349.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Deirdre McCann is a Reader at Durham Law School, University of Durham (UK). Her research is in the field of labour law and policy at the domestic, European Union and international levels. Her work has a particular focus on the regulation of precarious work, the measurement and comparison of labour law regimes and the influence of state norms in low-income settings. Her publications include Regulating Flexible Work (Oxford University Press 2008) and Regulating for Decent Work (Palgrave 2011) (with Sangheon Lee).

Deirdre is a former official of the International Labour Office in Geneva. She is a founder and co-chair of the organizing committee of the international research Network on Regulating for Decent Work, and a member of the editorial board of the Industrial Law Journal and the advisory committee of the Labour Law Research Network (LLRN). In 2015, she was awarded a Leverhulme Research Fellowship for a research project on Creative Uncertainty? Labour Market Regulation in a World of Doubt.

For more details about the UFW project visit the website or Durham Law Policy Engagement contact Deirdre at deirdre.mccann@durham.ac.uk or follow on Twitter, @LabourRights_.